The growing Santa Fe freight depots and warehouses created to serve the citrus industry’s shipping needs determined the area’s economic character for most of the next century, and is responsible for the architectural flavor of the Arts District structures that have survived earthquakes, flood and fire. The single room hotels for rail workers to the northwest (and the growth of Little Tokyo to the west, and Chinatown to the north) created a mix that was distinctly working class, cosmopolitan and a bit exotic in a manner similar to other West Coast urban centers.

By World War II, the citrus groves had been replaced by factories and the rail freight business was giving way to the more flexible trucking industry. The area had taken on a distinctly industrial character that was already growing seedy around the edges. Over the next twenty years, many of the independent small manufacturers had either been absorbed by larger competitors, grown too big for their quarters – or simply failed – and an increasing number of vacant warehouse and former factory spaces contributed to a dingy, decaying urban environment typical of most aging big American cities of the era.

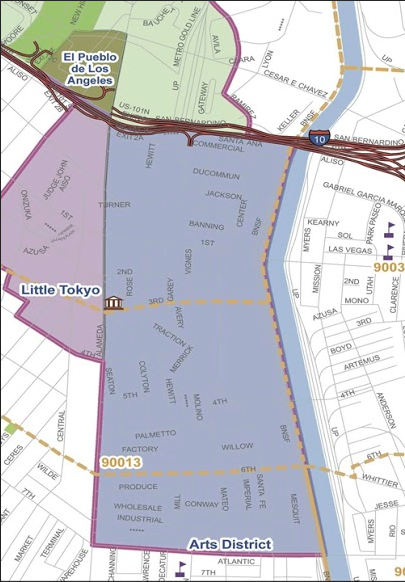

In the late 60s and early 70s a handful of determinedly urban-minded artists saw opportunity in the empty warehouses and began colonizing the area– converting former industrial spaces into roomy working studios, renting space for as little as a nickel a square foot and carving out living quarters, literally inventing the concept of live-work spaces. The City of Los Angeles eventually acknowledged the reality of the situation and in 1981 passed the Artist in Residence ordinance, which allowed artists to legally live and work in industrial areas of downtown Los Angeles.

Art galleries, cafes and performance venues opened as the residential population grew and although they are mostly a transient phenomenon, they have assumed mythical status among the urban pioneer population. Al’s Bar on Hewitt just off Traction, in particular, served up groundbreaking punk rock from the mid-70s through the beginning of the new century, introducing generations of Angelenos to dozens of emerging groups (among them, Pearl Jam). The Atomic Cafe on 1st Street at Alameda was a popular artists’ haunt in the late 60s and early 70s. Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) created pioneering post-modern exhibitions at its gallery space on Industrial Street. Riverrun, on Traction, created a regular series of challenging conceptual installations.

Bedlam, on 6th Street (and later, briefly, in the former premises of Al’s Bar) created one of the most successful and long-lived true salons on the Left Coast, featuring drawing workshops, art installations, theater, live music and a much celebrated speakeasy that is still sorely missed. Dangerous Curve, on a dangerous curve of 4th Place between Mateo and Molino, was a particularly engaging venue that offered exhibitions of artists whose work was often difficult to categorize. It was truly a pioneer in pushing the boundaries of gallery exhibitions. The Spanish Kitchen, a warehouse space on Third near Traction, was home to series of happenings, events, raves, installations and blowout parties. Coccola (later known as the 410 Boyd St. Bar and Grill), the legendary artists’ bar just west of the Arts District, lives on as Escondite.

The institution that was for many years the heart of the Arts District was Bloom’s General Store, presided over by the colorful and irascible Joel Bloom– a veteran of Chicago’s Second City who became an early advocate for the community and who is remembered as The Arts District’s once and only unofficial mayor. Bloom passed away in 2007, but his memory is honored with a plaque from the city declaring area around Third, Traction and Rose to be Joel Bloom Square, which is, appropriate to the eccentric nature of the community, actually a triangle.

Cornerstone Theater, a nationally celebrated enterprise that brings community theater to locations all around the country, still resides on Traction Avenue. Around the corner, on Hewitt at 4th Pl., the non-profit ArtShare offers lessons in art, dance, theater and music to urban youth and features a small theater often used by Padua Playwrights, one of the most distinguished theater enterprises in the U.S. Padua regularly stages groundbreaking plays around the city, often in non-traditional environments, and hosts playwriting workshops that continues to nurture rare and exquisite new talents.